Learning safety guardrails for surgical robotics

Ami Beuret

December 2025

Robotics, and even more so, surgical robotics, are settings where the drawbacks of usual reinforcement learning are pronounced.

We cannot afford to learn by trial and error. Mistakes could be costly or even life threatening. Even if we train our models in high-fidelity simulations, it remains quite sample inefficient to train safe policies. Unlike games or simulated environments, reward or cost signals might not be even clearly defined.

What we have, in many hospitals, is a growing pile of recorded operations: videos, robot states, actions, and outcomes. Mostly safe; mostly unlabeled; rarely optimal, and often partially observed and high-dimensional such as RGB, X-ray or ultrasound images.

This post is about what to do with this reality. Can we learn safe policies from such offline data with minimal annotation and interaction? Can we infer safety constraints that generalize beyond the demonstrated behavior?[1]

This post is less about the technical details (which are in the linked papers) and more about the overall design choices and reflections on why they were made. If you are familiar with the topics discussed, jump to the discussion or the future work at the end, the rest is background and details.

In what follows, first I describe a simple offline-first pipeline briefly and explain why some design choices were made to tackle the issues above. Then in the discussion section I share more opinions and personal experience on the topic.

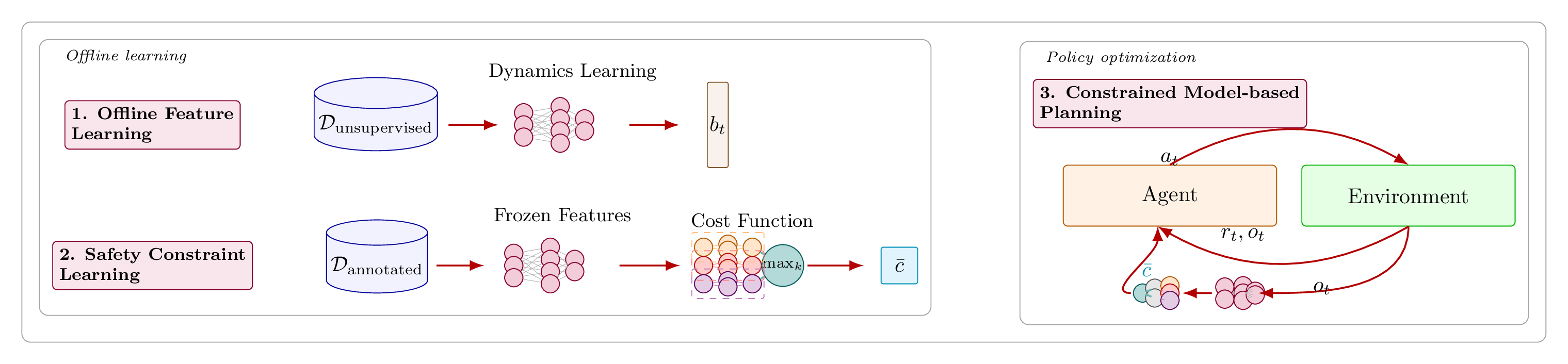

The pipeline has two complementary ways to learn constraints from demonstrations:

- A geometric approach using convex polytope approximation

- A preference learning approach using a small number of pairwise preference labels, without requiring unsafe trajectories.

Then using these learned constraints (from either of these two approaches), we can enforce safety during model-based planning to learn safe policies, either offline, or online with minimal interaction.

If there is one thing I want you to take away from this post, it is this: consider seriously the suggested pipeline. It might help you avoid some pitfalls.

The problem formulation

A useful formalization of surgical procedures is a constrained Markov decision process (CMDP) [1]: maximize task return (reach a target, orient an instrument, track a path, complete a subtask) while keeping expected cumulative cost below a budget (e.g., tissue strain, force limits, or distance to vessels). We then say a policy is safe if the expected cost is below the budget.[2]

This CMDP framing matters because it separates two jobs that are often conflated:

- Learning how to do the task.

- Learning what we are not allowed to do.

We are interested not only in learning safe policies, but also in inferring safety constraints from data. This is important because in many surgical settings, we do not have explicit cost functions or safety constraints defined upfront, or they are complex and difficult to model explicitly. Instead, we have demonstrations of safe behavior, and we want to extract constraints that can guide future decision making.

The pipeline

The pipeline has three components. Both constraint-learning approaches plug into the same middle block.

1) Offline feature learning for partial observability

Real surgical sensing is partial. We see images, not necessarily full state. A single frame is not enough; the belief over what is happening matters [2].

Concretely, we use a recurrent state-space model (RSSM) [3] trained from recorded trajectories. It learns to compress high-dimensional observations into a latent state and to predict forward under actions. It is intended to approximate the true belief state by capturing history dependence in its recurrent state.

By learning this latent space, not only we handle partial observability for the sake of task performance, we also reduce the required number of safety labels significantly down the road. Instead of learning constraints in pixel space, we learn them in this rich latent space. These latents also capture safety-relevant features, making constraint learning easier.

2) Offline constraint learning in the latent space

Given a learned latent state, we want a constraint model that can be enforced during decision making. We learn this model offline from demonstrations and a small amount of annotation, depending on which route we choose:

- Polytope learning: learn a conservative safe set from labeled safe and unsafe trajectories.

- Pairwise comparisons: learn a conservative cost from pairwise comparisons, without requiring unsafe trajectories.

We will cover both in detail below.

3) Constrained model-based planning and policy optimization

Once we have a world model and a constraint model, we can keep interactions minimal:

- Roll out imagined trajectories in latent space using our world model (dreaming).

- Optimize actor and critic against predicted reward while respecting constraints.

- If we go online at all, it is in a controlled, model-based way that reduces the number of real interactions significantly. It also enables many existing safe planning or exploration methods to be plugged in.

If safety and sample efficiency matter, model-based planning is the right choice. Model-based planning enables us to evaluate candidate policies in imagination or tree search, reducing real-world interactions to a minimum. It also enables safer exploration strategies.

That’s it. That is the pipeline. If you are curious about the constraint learning options, read on. Otherwise, jump to the discussion section for high-level takeaways.

Constraint learning approaches

Now let’s dive into the two constraint learning options.

Option A: learning a conservative fence with convex polytopes

We know that the convex hull of safe trajectories defines a safe set[3]: if we stay inside, we are safe. If we step outside, we might be unsafe [4]. This approach is a conservative one: it may label some safe points as unsafe, but it will not label unsafe points as safe. Exactly what we want for our high-stakes setting.

Now computing the convex hull in high dimension is practically intractable. For this, we approximate it with a K-facet polytope using a Convex Polytope Machine (CPM) [5]. We lose the cherished guarantees of the original convex hull[4], but we gain tractability, scalability, and additional way of controlling conservatism via a margin parameter.

CPM learns a set of hyperplanes that define a convex region. Safe points are pushed to lie inside; unsafe points are pushed out. The result is an approximation of the safe set that is tractable to learn and enforce. Each K facet corresponds to a linear constraint that can be integrated into model-based planning.

Option B: learning constraints from comparisons

Sometimes we cannot label costs. Sometimes we cannot even obtain unsafe examples. But we can often ask a surgeon a simpler question:

Which of these two trajectories is safer (or more acceptable)?

That is the core of the preference-learning option [6]. It uses a small set of pairwise comparisons to train a cost decoder in the latent belief space . A standard model for this is Bradley–Terry which assigns more probability to trajectories with lower predicted cost. This makes annotation realistic: the expert does not have to assign numbers, only orderings. This is also how we get around the lack of unsafe examples: we can compare two safe trajectories and still learn which one is safer.

Now in the low-data regime, we must be careful about uncertainty and underestimation of cost. Here we should be explicitly pessimistic.[5] We use an ensemble of cost decoders and define a pessimistic cost by taking the maximum predicted cost across the ensemble [7]. If the ensemble disagrees, the pessimistic cost rises. That is exactly what we want: unfamiliar situations are treated as potentially risky.

Above was a short summary of both constraint learning options. Once we learn the constraints, as already mentioned, we can use them during planning to learn safe policies.

Discussion and takeaways

Once we put safety first, many downstream design choices become clearer. Here are some reflections on the main decisions we made and why.

1) Problem formulation: explicit constraints [6]

Framing surgical decision making as CMDPs is, in my view, strictly better than the most common alternatives in prior work (implicit penalties, reward shaping, or “safe” heuristics baked into the reward). The reason is control and clarity: a CMDP forces you to separate task performance from constraint satisfaction, and it let us tune this tradeoff explicitly via budgets rather than implicitly via reward weights.[7]

Unfortunately at the time of writing, there are still very few instances of works that abstract these surgical tasks as CMDPs. Most prior works either ignore safety entirely or conflate it with reward by penalizing unsafe events.[8] Mixing safety constraint and task reward is problematic because it buries safety under task performance and makes tradeoffs implicit and hard to control.

That said, I don’t think CMDPs are enough. They enforce constraints only in expectation. In safety-critical robotics, expectations may be too weak, because rare-but-catastrophic events can remain acceptable in expectation while still being unacceptable clinically. This is why, long-term, one should consider stricter safety formulations such as Chance Constraints, Control Barrier Functions or similar approaches.

CMDPs are still a good starting point: they are tractable and make the “safety vs. performance” tradeoff explicit. One could see them as a way of steering agents to safe behavior, with the understanding that stricter safety guarantees may be layered on top.

2) Learning constraints is often more practical than learning rewards

Constraints transfer better across tasks and are less sensitive to stylistic variation. The heterogeneity of demonstrations is less of a problem when learning constraints than when learning rewards, because we only care about the boundary between safe and unsafe behavior, not about explaining all demonstrated behavior with a single reward function, as is usual in inverse reinforcement learning.

Another benefit of learning constraints is that, depending on the approach, it enables us to relax optimality assumptions on the expert demonstrations.[9] We do not need to assume that the expert is (near-) optimal with respect to some unknown reward as required for most inverse reinforcement learning methods; we only need to assume that expert data covers safe boundaries well enough to learn constraints. This is a more realistic assumption in practice. This was one of my motivations for exploring constraint learning in the first place as I had suffered enough trying to make reward IRL work in practice.

Another reason why one might prefer learning constraints over rewards is trust. Assume that we are given a ground truth reward function that perfectly captures the task. There is high chance the learned policy will outperform human experts on that reward. But the question that often arises is: will it do so safely? If the reward does not capture all safety aspects perfectly, the learned policy may exploit loopholes in the reward to achieve high return at the cost of safety. Clinicians and patients might not trust such policies. But if safety constraints are learned explicitly from human demonstrations, they may be more likely to trust that the learned policies will respect safety boundaries, even if they outperform humans on task return. I learned this lesson firsthand when working on some tasks where the agents were able to outperform humans on reward by performing unintuitive maneuvers. They were effective, but not trustworthy to the clinicians.

I’m not arguing against reward learning in general; just emphasizing to learn constraints from demonstrations when safety is the main concern. It’s easier, more robust, and more practical in many cases.

3) With explicit safety, model learning becomes hard to avoid

If constraints must be enforced during planning then some form of model learning is almost inevitable. Purely model-free, on-policy methods (e.g., vanilla PPO) are often a poor fit for high-stakes domains unless paired with strong safety mechanisms. Some safety formalisms even explicitly require a dynamics model; but even within the CMDP framing, a learned dynamics model offers several advantages such as safe exploration, or offline learning from small annotated datasets (as we have shown) where we use unlabeled data to learn the world model.

If you can roll out trajectories in a learned world model, then the number of real interactions needed to evaluate candidate policies can drop dramatically, and in the purely offline case, it can disappear entirely.

Model-based planning also helps avoiding Q-learning scalability issues due to bootstrapping errors, especially in offline settings [9]. Model learning is generally more scalable and although might still suffer from compounding errors, it is often more robust than many alternatives.

4) Planning in latent space is not optional

Planning directly in pixel space is generally impractical, but ignoring image observations is also unrealistic in surgery. Many prior works avoid the issue by assuming access to low dimensional state (poses, forces, handcrafted features).[10] That is convenient for algorithm development, but it does not reflect how clinical systems are instrumented: endoscopic RGB, X-ray, fluoroscopy, etc., are central sensing modalities and are not going away.

So the practical position is: learn the right latent space, and do the learning there. This is not just about compute efficiency; it is about turning a partially observed, high-dimensional control problem into something that can be optimized robustly. Once we map observations to a latent, downstream learning (constraint learning, planning, uncertainty estimation) become easier. In this setup we want to learn a latent state that summarizes history. If the learned latent is a sufficient statistic of history, approximating the true Bayesian belief state, then the planning in latent space approximates planning in the corresponding belief MDP, rendering the problem effectively Markovian: the better the approximation, the closer we get to an MDP.

Empirically, RSSM world models have been particularly effective for this setting: the recurrent belief state can capture the history dependence needed for partial observability, and the latent can encode safety-relevant structure even when trained only with reconstruction and dynamics losses (i.e., without explicit cost signals), at least for the classes of constraints we cared about. This makes it practically a self-supervised approach with respect to safety signals. With additional supervision, one could imagine learning even better safety-relevant latents.

That being said, it does not mean RSSMs are optimal; in the absence of any safety signal, these features are probably a poor choice because even true state space could be suboptimal. There may be better inductive biases or representation objectives (maybe forward-backward representations [10]?) for constraint-relevant latents, and there is room for improvement in how these representations are learned. What matters is the principle: learn a latent belief space that captures safety- and task-relevant features, and plan in that space.

5) Choosing the right constraint learning approach

The two constraint learning options above are not mutually exclusive, and they are not exhaustive. Which one is appropriate depends on what supervision is available and what failure modes you care about. I tend to choose the preference-based approach as a default, as it seems less sensitive to hyperparameters and generalizes better in practice, but both have their merits.

-

Convex polytope safe sets can be attractive when you can label safe vs. unsafe segments. One advantage is interpretability: the constraint is a geometric region, and violations correspond to leaving that region in latent space. In addition, at least theoretically, this approach should learn multiple unknown constraints, but in practice we have not fully tested this multi-constraint interpretation.

One current drawback is scalability. Increasing the number of facets increases representational power, but it also increases optimization complexity at planning time. In our constrained planning setup, more facets effectively means more constraint terms and, depending on the solver, more Lagrange multipliers or more complex constrained updates. At the time of writing, it is unclear how to optimize with large numbers of facets (or learned costs) during planning without introducing significant complications such as competing objectives and instabilities.

One limitation of the CPM-based approach is that it requires both safe and unsafe examples to learn the polytope boundary. One could design alternative polytope construction algorithms that work from safe examples alone (without being too conservative), or augment the dataset by generating artificial unsafe examples from simulations. This would be particularly attractive in clinical settings where collecting real unsafe demonstrations is undesirable.

One reason I’m less enthusiastic about polytope methods as a default is that we lose all theoretical guarantees with the approximations we make for tractability. In practice, the learned polytopes work well, but then one could argue that preference-based costs work well too, and they are more flexible. If someone shows that polytope methods do indeed capture more than one constraint reliably, that would make them more compelling.

-

Preference-based constraint learning can be the better default when unsafe examples are unavailable. Pairwise comparisons tend to be more natural for clinicians than absolute scoring, and preference learning has also proven effective at scale in other domains.

The main concern is coverage: learning a safety boundary from preferences over trajectories generated by only safe policies can underestimate cost in parts of the state space never visited. In practice, large and diverse datasets can mitigate this, but it remains a conceptual weakness if the dataset fails to cover near-boundary behavior. Another subtle issue is conflict: if preferences implicitly mix multiple unknown costs that sometimes disagree (e.g., “minimize tissue stress” vs. “minimize procedure time”), the learned cost may become context-dependent or inconsistent unless the model and labeling protocol explicitly represent that structure.

It would be valuable to test these ideas with real preference data from experts, including disagreement analysis across surgeons and across clinical contexts. That would reveal whether the learned constraints reflect stable “guardrails” or whether safety is inherently multi-objective and context-conditioned in a way we must model explicitly.

In short, consider seriously the suggested pipeline: offline feature learning, offline constraint learning, then constrained model-based planning. It minimizes real interactions and annotation while ensuring safety.

Future work

From here there are many directions to explore. Some that I find particularly interesting:

- Stricter safety guarantees: CMDPs are a start, but not enough for high-stakes settings. Chance constraints, CVaR, or Control Barrier Functions could be next steps.

- Better latent representations: RSSMs work well, but are they optimal for all types of safety signals we care about? Are there better inductive biases or objectives for learning safety-relevant latents?

- Alternative polytope learning methods: can we learn conservative polytopes from safe data alone? Can we scale to many facets without complicating planning?

- Multi-constraint learning: real surgical procedures have many safety constraints that may conflict. Learning multiple constraints explicitly, and reasoning about tradeoffs between them, is an important next step.

- Real expert data: testing these methods with real clinical demonstrations and preference labels would validate their practical utility and reveal real-world challenges.

- Real deployment: integrating learned constraints into real surgical robotic systems and evaluating their impact on safety and performance in clinical settings is the ultimate goal. One could start by only providing safety suggestions and context to human operators rather than full autonomy.

If you are interested in any of these directions, feel free to reach out!

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Yarden As, Yunke Ao, and Andreas Schlaginhaufen for their thoughtful comments and discussions on this post. Their feedback, questions, and insights have been invaluable in shaping the ideas and clarity of this work.

Footnotes

[1] Of course, the same question applies to inferring reward functions from data, but that is outside the scope of this post. ↩

[2] Throughout this post, I use the term safe both in the formal CMDP sense (expected cost below budget) and in the more general sense of "not causing harm" or "respecting clinical safety constraints". It might be imprecise or confusing to conflate these meanings, but I hope the context makes it clear which sense is intended. ↩

[3] Actually, to be precise, we know that convex hull of feature expectation of safe policies define a safe set, under some assumptions, such as linearity of costs in features, correct estimation, etc. See Lindner et al. [4] for details. ↩

[4] There are also other reasons for losing these guarantees, for example our learned features might not be linear in the unknown costs. ↩

[5] Note that in the polytope-based method, pessimism is built in by design. ↩

[6] One might argue that "reward is enough" [8] and that any safety constraint can be encoded in a sufficiently well-designed reward function. While this may hold theoretically under certain assumptions, it is beside the point for our purposes. In high-stakes settings, interpretability, explicit control over safety tradeoffs, and the ability to audit constraint satisfaction separately from task performance are important requirements. ↩

[7] Of course, in practice, choosing the right budget value can be non-trivial. Without units or interpretable semantics attached to the cost function, a budget threshold is just a number, and tuning it still requires domain insight or iterative calibration against safe behavior. ↩

[8] There are works that incorporate explicit constraints or verification layers, but they are not yet widespread. ↩

[9] Safety certification does not rely on reward-optimal demonstrations, but obtaining guarantees about downstream reward performance typically does require additional assumptions (coverage and, in some analyses, noisy/near-optimality). ↩

[10] That said, these agent states such as poses and forces still have their merits, especially when interpretability is important. One could imagine a hybrid approach where we also predict these from our latents (similar to how we predict reward) so that we could use these features directly for some of our safety learning and constraint enforcement. ↩

References

[1] Altman, E. (1999). Constrained Markov Decision Processes. CRC Press. [Book] ↩

[2] Kaelbling, L. P., Littman, M. L., & Cassandra, A. R. (1998). Planning and Acting in Partially Observable Stochastic Domains. Artificial Intelligence, 101(1-2), 99-134. [Paper] ↩

[3] Hafner, D., Lillicrap, T., Ba, J., & Norouzi, M. (2020). Dream to Control: Learning Behaviors by Latent Imagination. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). [Paper] ↩

[4] Lindner, D., Turchetta, M., Tschiatschek, S., Berkenkamp, F., & Krause, A. (2024). Learning Safety Constraints from Demonstrations with Unknown Rewards. Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS), PMLR 238:1378-1386. [Paper] [arXiv] ↩

[5] Kantchelian, A., Tschantz, M. C., Huang, L., Bartlett, P. L., Joseph, A. D., & Tygar, J. D. (2014). Large-Margin Convex Polytope Machine. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). [Paper] ↩

[6] Bradley, R. A., & Terry, M. E. (1952). Rank Analysis of Incomplete Block Designs: I. The Method of Paired Comparisons. Biometrika, 39(3/4), 324-345. [Paper] ↩

[7] Lakshminarayanan, B., Pritzel, A., & Blundell, C. (2017). Simple and Scalable Predictive Uncertainty Estimation using Deep Ensembles. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). [Paper] ↩

[8] Silver, D., Singh, S., Precup, D., & Sutton, R. S. (2021). Reward is enough. Artificial Intelligence, 299, 103535. [Paper] ↩

[9] Park, S., Frans, K., Mann, D., Eysenbach, B., Kumar, A., & Levine, S. (2025). Horizon Reduction Makes RL Scalable. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). [Paper] ↩

[10] Touati, A., & Ollivier, Y. (2021). Learning One Representation to Optimize All Rewards. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). [Paper] ↩

Related Publications

The arxiv versions will be added here as soon as they are online.